We owe our cohesive street naming and numbering system to Edward P. Brennan. Brennan was the chairman of the City Club of Chicago's Committee on Street Names. His vision included three changes:

- The house and building numbering system should tell you where you are relative to the Loop.

- Streets should be named the same throughout their length.

- Street names should be simplified.

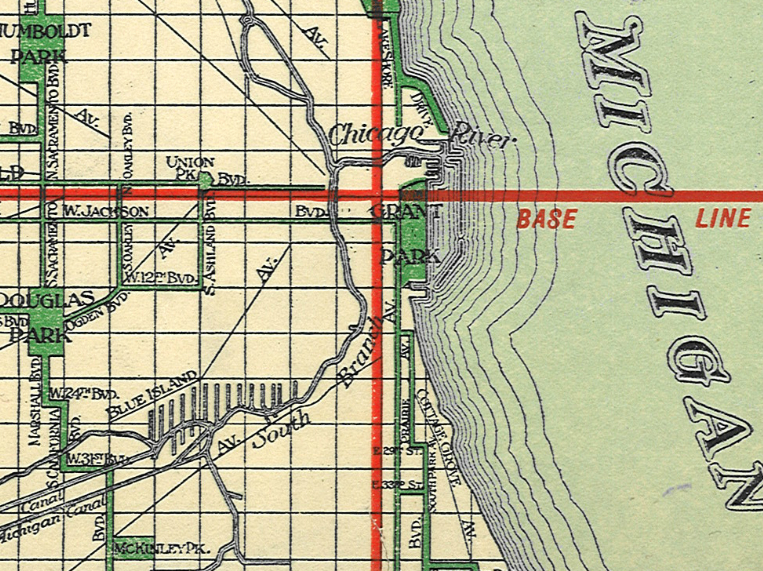

In order to rationalize the numbering system, Brennan came up with State and Madison as the baseline from which all streets were numbered. This consistent and reasonable system allotted for 100 house numbers per one-eighth of a mile, or a city block. You can easily tell how far you are from State and Madison by the house number. For example, if you are at 1901 W. Madison, then you are 19 blocks west of State Street. Within this numbering system, all even number houses are on the west and north sides of streets; odd numbers on the east and south. So at 1901 W. Madison, the building is on the south side of the street.

Prior to Brennan’s suggestion, houses were numbered haphazardly. Some were numbered beginning at the Chicago River branches. Some streets started numbering at their ends. This was not consistent either. For example, Willow started numbering at its east end. Wisconsin, the next street up, started numbering at its west end.

The street naming system was also a free for all before Brennan. Some streets changed names as they crossed the river. Wells ran north of the main branch of the Chicago River. On the south side of the bridge, it became Fifth Avenue.

Other streets changed names and house numbering with seemingly no rhyme or reason. Ann Street existed for a few blocks on the Near West Side. Between Randolph and Madison it was “South Ann”, between Randolph and Kinzie it was “North Ann” and then you crossed railroad tracks and the name changed to “Centre Street”. South of Madison, “Centre Street” started up again, but with house numbers that started over at 1 South. So 56 South Ann was across the street from 1 South Centre. Today, these house numbers would all be located on Racine.

Brennan proposed that each street should keep the same name throughout its span. To eliminate duplicate street names, such as a dozen streets named “Lincoln”, Brennan drew the city on a piece of graph paper. In his plan, the north-south streets and east-west streets are called the same name for their length. Even if a street dead-ended and started-up blocks later, it would still be called the same thing as long as it was in the same line.

The last piece of plan was to simplify the street names. On the West Side, there were numbered avenues that ran north-south. So 40th Ave. intersected with 40th St. Brennan planned to change these north-south numbered streets to unique names that began with the same letter. Just like you could use the "tens" place of a street number to know how far south you were from Madison, you could use the alphabet to estimate how far west you were from Indiana. All streets in the first mile west of the Indiana state line would begin with “A”.

Since much of the city was already built up, there was resistance to changing the names of nearly all north-south streets. Instead, using the alphabet initials to name streets really began on the west side, about 11 miles in. There you find streets such as Komensky, Karlov, Kedvale, and Keeler. A mile further west, you find Leamington, Laramie, Latrobe and Lockwood.

As a member of the City Club of Chicago, Brennan worked with the City Council’s Committee on Street Nomenclature and the Superintendent of Maps to implement his plan. A decade after Brennan first proposed them, the last of the house numbering changes took effect on April 1, 1911. In 1912, the City Council’s Committee on Street Nomenclature issued a Report on Street Nomenclature which included a 14-page suggested list of new unique street names, from Abbotsford to Azena, Zachary to Zypho, and everything in between. There is little explanation as to where names came from. You can trace some of the city’s more interesting street names, such as Mango, to this list.

Street name changes had to be approved by ordinance of the City Council, or in other cases, various park districts. It took many years for the duplicate and incongruous streets to be renamed. Brennan kept scrapbooks of this interesting bit of municipal history. These scrapbooks are now at the Chicago History Museum. Near the end of his life, Brennan was recognized for his service to the city. After he died in 1942, the City Council named a street, S. Brennan Avenue, in honor of Brennan's work.

Brennan may have led the city to orderly street names and house numbers, but all these changes can confuse modern researchers. To find out more about Brennan's legacy, see my next post.

Add a comment to: Not Lost? Thank Edward Brennan