The fruit and vegetable trade in Chicago may not have been lauded in poems—Carl Sandburg called Chicago the "hog-butcher for the world" not the "pumpkin-supplier." But the produce trade of the South Water Street Market was, and still is, an important center of agricultural trade and commerce.

According to a history of The South Water Street Market by Frederick Rex, no one can remember when the market started.

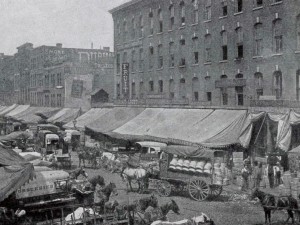

South Water Street was formerly the first street south of the main branch of the Chicago River. Along the river, goods were loaded off ships and barges and brought to the market stalls of South Water Street. In his 1918 book, The Chicago Produce Market, Edwin Griswold Nourse said, “South Water Street is sometimes referred to as ‘the busiest street in the world.’ This, if true, was not entirely to its credit. Some of its ‘busy-ness’ is mere wasted effort.”

Congestion was not the only problem for South Water Street. While city ordinances regulated the public market on Maxwell Street, Nourse noted, “The city takes no official cognizance of this use of the street and no fee is charged nor is any market master in attendance, though the policeman from the beat makes a point to be on hand.”

This free-for-all style of trade posed problems for the produce business. In contrast, the Union Stockyards created a way for livestock to come to Chicago by rail, and provided a place to unload the livestock, pens to keep them in, and a mechanism to trade and ship them to other destinations.

Facilities were much poorer for produce. After arriving in Chicago by rail or water, the refrigerated or heated warehouses to keep the fruits and vegetables fresh in the summer and from freezing in the winter were scattered and hard to reach.

“Perhaps the most striking feature of this matters is that in this, the greatest railway center in the world, the produce market—likewise one of the greatest in the world—is provided with no special terminal facilities. Far from having a central terminal building where perishables could be delivered—direct to heated or cooled rooms when necessary—Chicago has not even that centralization of its deliveries which is possible under the New York system…”

South Water Street was definitely on the minds of Edward Bennett and Daniel Burnham while they were producing the Plan of Chicago. They proposed bi-level streets along the river. This would alleviate some of the “busy-ness” that Nourse felt was wasted effort. Goods could be unloaded and moved on the lower level, and traffic and pedestrians could move unimpeded on the upper level.

The 1909 plan began a 15-year transformation of the South Water Street Market into the engineering marvel that is Wacker Drive. My next post will discuss how the South Water Street Market moved and took its name with it.

Add a comment to: South Water Street Market: Center for Produce Trade