Have you ever wondered what a street named Artesian Avenue is doing tucked between the likes of Western and Campbell Avenues? In 1863 a clairvoyant convinced A.E. Swift and Thomas Whitehead that Chicago was the perfect place to drill for oil.

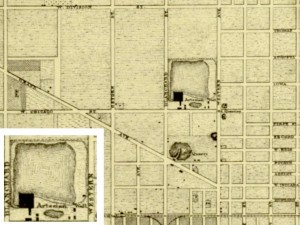

Here is the story as told by materials in Special Collection’s West Town Community Collection, Andreas History of Chicago and History of the Chicago Artesian Well. The two men bought 40 acres of empty prairie at Chicago and Western Avenues and began drilling at the spot the clairvoyant pointed out. Encouraged by traces of oil, they persevered.

In November of 1864 at 711 feet, they struck a gusher of water. It shot 80 feet into the air. They had an artesian well.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s definition is: “The word artesian, properly used, refers to situations where the water is confined under pressure below layers of relatively impermeable rock.” In layman’s terms, you drill a well and water shoots out. Since “artesian water” sounds so much better than “well water,” many people use “artesian” for any deep well.

Chicago’s artesian water comes from sloping layers of rock that act as pipes from lakes and rivers at higher elevations in Wisconsin. A catalog search on “groundwater northeastern Illinois” yields a number of technical publications explaining the process.

Perhaps a little disappointed, the two men's thoughts turned to what to do with this bonanza. Everybody came to marvel and offer advice. They could sell pure water at half the cost of the city’s contaminated water supply. Hook it up to a fire hydrant and you had a perfect high-pressure water source. It was a little smelly, so maybe it had medicinal properties. Best of all, it was a source of perpetual energy.

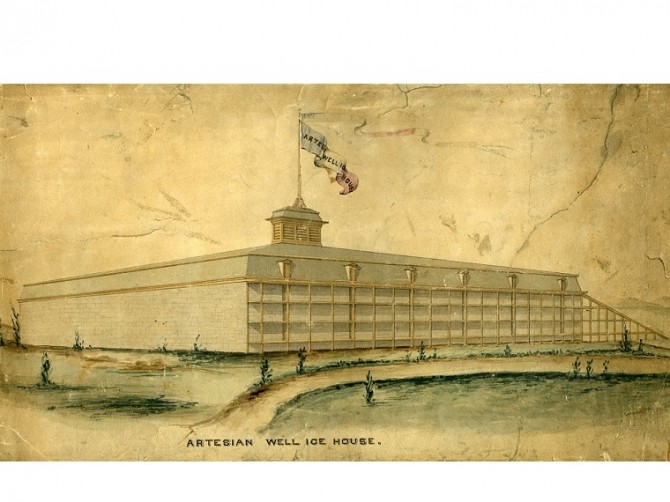

The spirits still said there was oil, so the two men used a waterwheel powered by energy from the first well to drill a second well next to the first. After again striking water, they sold out. The new company set up a sanitarium and sold water locally, but their main business evolved into cutting and selling ice from a 25 acre pond.

Many other people drilled wells through even deeper layers of rock. Naturally, with all of the water being taken out, the pressure diminished. By the 1890s water no longer bubbled out of wells. According to The Artesian Waters of Northeastern Illinois, by 1919 the groundwater needed to be pumped from hundreds of feet below the surface. By then there were about 125 large industrial wells. The Stockyards area had the most wells.

In the 1890s, using perfect timing, the Artesian Ice Company subdivided and sold their land for residential development. The wildcat well apparently proved profitable to the very end. Now a few suburban towns still get their water from deep wells, but the days of water shooting out of the earth are long over.

Add a comment to: Artesian Wells: Technology That Changed Chicago