After the breakneck pace of innovation from 1864 to 1890, communications technology changed more slowly. In the early 20th Century, citizens acquired telephones at a rapid pace. Since direct dial was still in the future, you simply picked up the phone and told the operator the nature of the emergency.

Direct dial for Chicago was introduced in 1923, but did not extend citywide until 1960. Even then, 911 was unnecessary, you just dialed zero for the operator—an instruction I remember from my childhood. The actual numbers for Chicago were POLice 1313 and FIRe 1313. We even have a magazine with the title Police "1313".

For those without telephones, alarm boxes remained on the street. Police officers could also call back to their stations from the boxes. This system continued to work flawlessly for the Fire Department, but one important police communications link was missing. The police had no way to dispatch patrol officers to the scene of a crime.

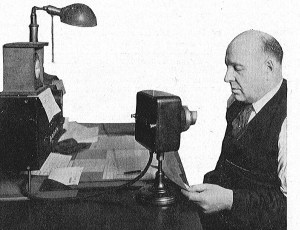

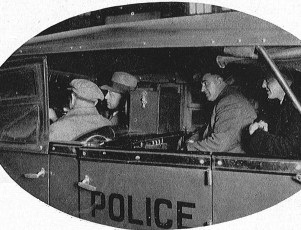

The 1929 Annual Report documents the first experiment with radio. Radio station WGN interrupted its broadcasts with reports of crimes in progress. Radio-equipped police automobiles would then rush to the scene.

The experiment was a success and the police purchased their own radio system. A Tribune article notes that even before the system was operational, crooks had been apprehended with their own radios set to police frequencies. By the end of 1930, the police operated three radio stations. The 96 radio-equipped cars were able to get to the scene in three to five minutes. Two-way radios were installed in 1939.

Officers on foot patrol began carrying walkie-talkies in the late 1960s, largely eliminating the need for the police alarm boxes. The original radios were heavy and unreliable. Within a few years they became a lightweight essential part of the police officer’s equipment. To the envy of other cities, Chicago even developed radios disguised as beer cans.

Add a comment to: Calling 911, 1900-1970: Technology That Changed Chicago