By the 1960s, most of the country had switched to direct dial telephones. Telephone operators were on their way out. In areas such as Chicago’s suburbs, there are hundreds of police departments and fire districts. The service boundaries are rarely clear. You needed to find a telephone book, hope your dog hadn’t eaten the first few pages, and decide on the right number.

The need for a simple emergency number was apparent. In 1968, 911 became the national standard. For Chicago, 911 calling started in September 1976. From the start, Chicago had a technologically advanced system. The operator could see the caller’s telephone number. Chicago’s system has continued to be a technological leader and now dispatchers have an sophisticated computerized information and dispatch system.

Even after 911 service started, fire alarm boxes remained on the street corners and the Fire Department continued to use its century-old, yet reliable, fire telegraph system called the Joker. In 1979, the fire commissioner complained that 90 percent of the alarms from corner boxes were caused by children pulling them to see what would happen. Workers began removing the 3,600 boxes and added a radio-based system.

The next video, although low resolution, shows the juxtaposition of operators watching video monitors and sending alarms with a manual telegraph key.

The Municipal Code continues to require some theaters and schools to have their internal fire alarm systems hooked into a pull type alarm near the main entrance. Thus, you can still see functional red pull type fire alarm boxes in Chicago. The University of Chicago Police installed pull type police alarms on the streets of their Hyde Park neighborhood.

False burglar alarms requiring police dispatch became a major problem in the late 20th century. Burglar alarms had become both cheap and sensitive enough to be set off by mice, the wind, etc. In 1994, there were about 300,000 burglar alarm calls. 98 percent were false. The city council passed an ordinance fining owners for repeated false alarms. The fire system was less of a problem, but still a concern. Only about 10 percent of the fire alarms from smoke detectors and sprinkler sensors hooked into the 911 system were false alarms.

Later in 1994, technologically challenged alarms struck again. The city began requiring carbon monoxide detectors in almost all of Chicago’s million dwelling units in October. The first generation alarms were too sensitive and most of them went off in the foggy month of December. 911 began receiving thousands of calls a night. Thankfully, this fiasco was never repeated.

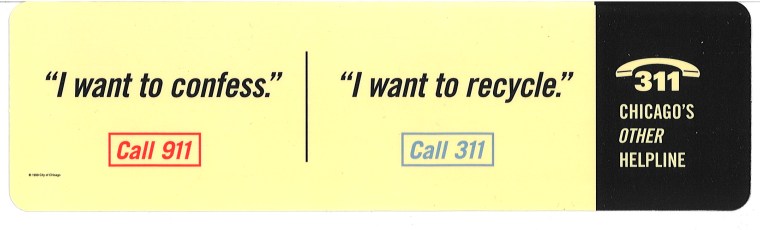

In order to relieve the pressure upon 911, operators the city instituted 311 service for non-emergencies in 1998. The 21st century saw the majority of 911 calls coming from cell phones. The city has coped with this change with even more advanced technology.

Add a comment to: Calling 911, 1970-2014: Technology That Changed Chicago