For thousands of years, people around the world have been storing winter ice and snow to use in hot summers. As Harvest of the Cold Months explains, ice storage was difficult, expensive and almost always a local effort. In the tropics, where ice was needed the most, it was never available.

Two Bostonians changed that. In 1806 Fredrick Tudor sent his first load of ice cut from a local pond to Martinique in the Caribbean. Most of the ice melted and sales were sluggish, but it had been proven that both the ship and the ice could survive the trip.

The next year he sent ice to Cuba. He faced a variety of troubles, including debtor’s prison, the War of 1812 and the fact that nobody in the tropics really knew what to do with ice. He dealt with these issues by constructing insulated ice houses, selling ice boxes (called refrigerators) to preserve the ice and instructing bartenders to give iced drinks at the same cost as warm drinks.

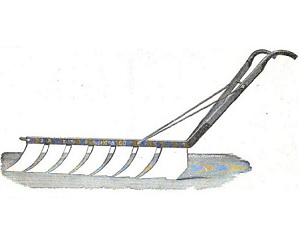

In 1827 Tudor joined forces with Nathanial Weyth. Weyth was a prolific inventor who invented dozens of the tools needed to make ice cutting a large industrial endeavor. The most important was his first invention, the horse-drawn ice plow which rapidly cut ice into uniform blocks. Before that, ice was hacked out with an ax or sawed by hand.

1833 saw Tudor’s most spectacular and profitable enterprise. He shipped a cargo of ice from Boston 16,000 miles to Calcutta. By the 1850s, Tudor and his American competitors were shipping ice to every part of the world. Although these foreign cargos made Tudor famous and rich, the real story was being played out in America by Tudor, Weyth and their imitators. By the 1850s enough ice was being cut, stored and shipped to allow almost every American to enjoy iced drinks, ice cream and a home icebox. This revolution is detailed in The Frozen-water Trade and The American Ice Harvests.

As the ice trade exploded, so did industrial uses. Lager beer depended on cool temperatures and thus ice throughout the brewing and storage process. Fish was not only shipped on ice, but in ice. In those days before shrink-wrap, a fish frozen in the middle of a block of clear ice was both a convenient shipping container and an eye-catching display. Chicago meat packing companies Swift and Amour set up networks of ice depots, cold storage warehouses and refrigerated rail cars allowing them to service the produce and fish markets in addition to meat. By the 1880s fresh California produce was available in London.

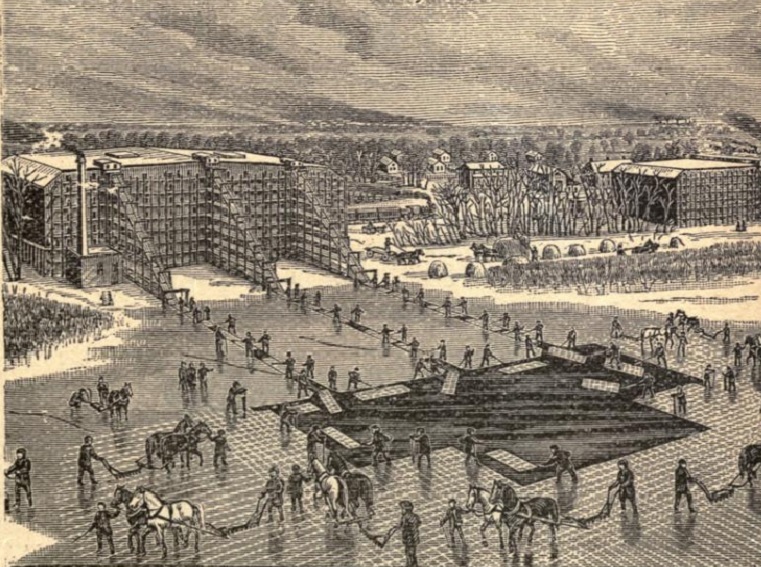

In theory, the ice harvesting business was simple. An 1893 how-to-book, The Ice Crop, required only 55 pages to explain the business before delving into ice cream recipes. An acre of water surface yielded a thousand tons of ice. A typical Chicago city block is five acres; thus the lakes and rivers of the northern states represented an unlimited supply. 150 farm laborers and a dozen horses employed in the slow winter season could cut and pack several thousand tons of ice a day.

In reality, the capital requirements were large. Although ice harvesting only took a few weeks, a large storage and distribution network was required. The weather had to cooperate. Ideal for the ice business were cold winters and hot summers. Warm winters meant no local ice. Large companies maintained ice harvesting operations in Maine and the Great Lakes to use when the more southerly ice crop failed, but the shipping costs would become enormous.

Add a comment to: Ice: Technology That Changed Chicago