After the Great Fire of 1871, a new generation of architects and engineers came to Chicago to build what were then the world’s tallest skyscrapers. Most of the buildings were architectural and financial successes. A few, including City Hall, the Post Office and the Board of Trade sank into the earth and had to be demolished.

Some of the notable buildings of the 1872-1900 period include the the Home Insurance Building (1885-1931) which was the first steel framed skyscraper, a number of the world’s tallest buildings of the time, and massive structures such as the Monadnock Block (1891), one of the world’s tallest buildings with masonry load building walls.

For a history of these building foundations we are indebted to an obscure, but fascinating, pamphlet by Ralph Peck entitled History of Building Foundations in Chicago. Another classic book, the History of the Development of Building Construction in Chicago is also useful.

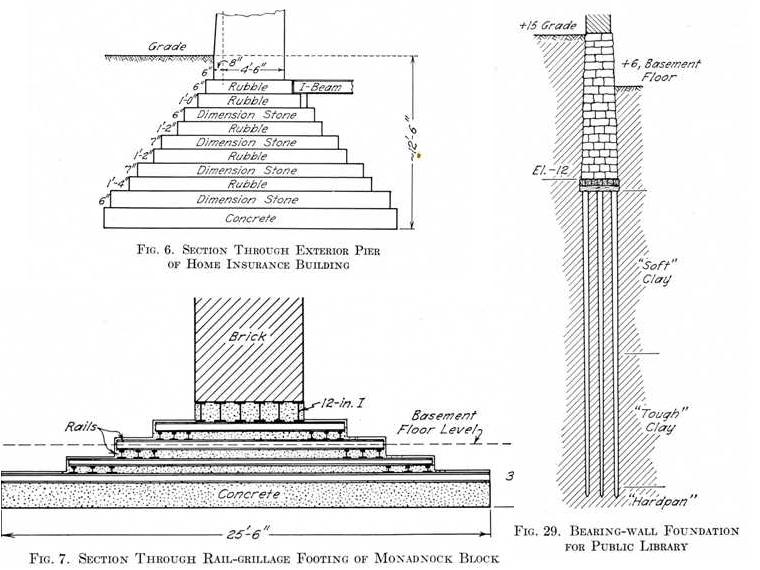

Downtown Chicago has about 15 feet of fill piled above the original ground level. The original ground was hard clay of varying depths. Below that are layers of soft oozing clay. About 100 feet down is limestone bedrock. Post fire architects tried to rest their buildings on the hard clay layer 15 feet down.

Many high rise buildings used a stepped stone mat for foundations. Stone mats had drawbacks. Such foundations were so massive that they filled the basement and extended into the street. They could weigh as much as the building itself, meaning the foundation was mostly holding itself up.

Improvements were made. Oak timbers and steel rails embedded in concrete allowed for thinner, lighter mats. Short wood piles driven into the hard clay layer were supposed to provide superior support. Mostly these worked. The buildings sank a few inches and came to rest.

Sometimes the engineering was off. Heavy parts of the buildings such as towers and exterior walls sunk faster than light parts such as interior columns. Sometimes methods which had seemed to work on previous buildings failed on new sites. Below the hard clay layer, the soft clay would ooze out sinking the building.

The Board of Trade (1884-1929) settled in such an alarming fashion that within 10 years a crack 10 inches wide developed in the exterior wall. The tower separated from the trading floor. After repairs were made, the building was used for another 25 years.

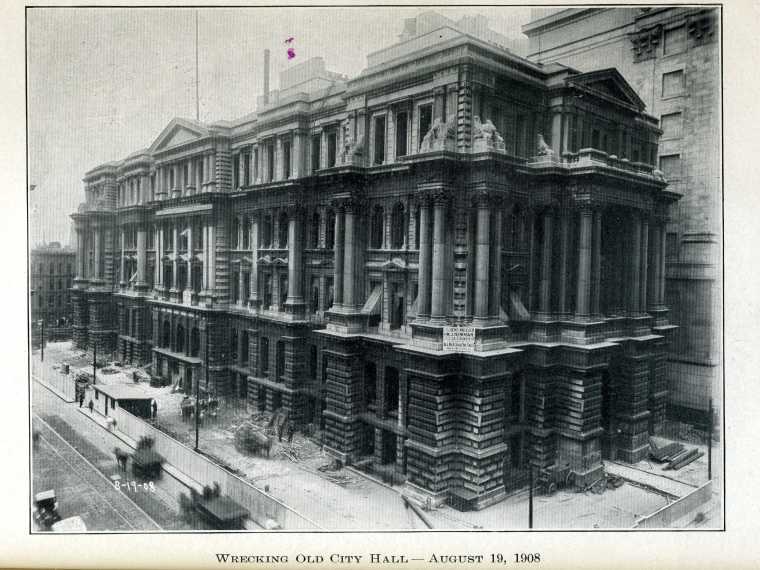

The old City Hall (1885-1908) settled so much that sewers, water and gas pipes broke, starting fires in the 1890s. Some officials blamed the heavy books in the Public Library on the fourth floor.

Other buildings alarmed their owners by rapidly sinking before finally coming to rest decades later. Examples still standing include the Monadnock Building which sank 21 inches in 50 years and the Auditorium Building which sank up to 2 feet in an irregular pattern causing structural damage.

By 1905 engineers had largely changed to deep piles and caissons. The problem was solved.

Add a comment to: Building Foundations Fail, 1870s-1900: Technology That Changed Chicago